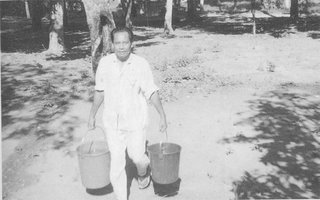

Said Zahari in forced exile on Pulau Ubin, 1979

Said Zahari in forced exile on Pulau Ubin, 1979SINGAPORE, April 24, 2007 (AFP) - A press freedom group called Tuesday for Singapore to reverse its ban on a film about a former political detainee.

Paris-based Reporters Without Borders (RSF) said the ban was "another authoritarian measure violating press freedom" in the city-state. Singapore banned the film on former detainee Said Zahari, calling it a"misleading and distorted portrayal" of his detention which could undermine confidence in the government.

The film "Zahari's 17 Years" was directed by Singaporean filmmaker Martyn See, who had earlier been investigated by police for making a film on opposition leader Chee Soon Juan.

"The ban on See's film must be lifted," RSF said in a statement.

"This act of censorship is all the more inappropriate and ridiculous as his films are available on websites," it said.

"We call for the liberalisation of the censorship and internal security laws that deprive Singaporeans of an environment favourable to free speech."

Singapore's ministry of information said See's film "gives a distorted and

misleading portrayal of Zahari's arrest and detention under the Internal Security Act in 1963."

It called the film "an attempt to exculpate himself from his past involvement in communist united front activities against the interest of Singapore."

In the film, the elderly self-exiled journalist, poet and author reflects on his 17 years in detention.

Singapore has often been criticised by human rights and media groups for maintaining strict political controls despite its rapid economic modernisation.

But the government says the strict laws are necessary to maintain law and order -- a pillar of the country's economic prosperity.

On Friday, producers of a Singapore film about a man and boy struggling with their mutual sexual desire said they had withdrawn it from public screening at the city-state's film festival.

The decision to withdraw "Solos" came after Singapore censors made three cuts to scenes depicting homosexual and group sex, the Singapore International Film Festival (SIFF) told AFP.

----------------------------------------

RSF's Press Release

AP report

1 comment:

For reference

http://www.straitstimes.com/portal/site/STI/menuitem.c2aef3d65baca16abb31f610a06310a0/?vgnextoid=7532758920e39010VgnVCM1000000a35010aRCRD&vgnextfmt=vgnartid:87b1871b50422110VgnVCM100000430a0a0aRCRD:STForumArcIOID:8e1ed6710e422110VgnVCM100000430a0a0aRCRD:STForumArcDate:1177538340000

April 25, 2007

Censors do explain decisions on films

I REFER to Mr Ken Kwek's article, 'Film bans: Detailed reasons, please' (ST, April 20), which states that the Board of Film Censors (BFC) does not give reasons when films are classified. Starting with his documentary, The Ballad Of Vicki And Jake, he asked why a drug-use sequence required an edit when a similar sequence in Protege was allowed.

Each film is assessed carefully. His documentary featured a female drug addict explaining and showing in detail the steps taken in consuming a drug using a 'crack' pipe. Under our film-classification guidelines 'instructive details of illegal drug use are not allowed'. This was explained to the film exhibitor, the Arts House.

The sequence in Protege, in comparison, was brief and permissible under the M18 guidelines.

Solos was submitted by the Singapore International Film Festival (Siff). It explores the homosexual relationship between a teacher and his student. The film contains prolonged and explicit homosexual sex scenes which exceeded an R21 rating.

BFC also consulted the Films Consultative Panel which recommended that the explicit homosexual scenes be removed. This was explained to Siff. Solos was not banned but Siff chose to withdraw the film.

Mr Kwek mentioned Zahari's 17 Years. The film was submitted this year by Martyn See for general screening. After careful consideration, the Minister for Information, Communications and the Arts decided to prohibit the film, under the Films Act, as it is against public interest.

Mica explained in its press statement on April 10 that 'The Government will not allow people who had posed a security threat to the country in the past to exploit the use of films to purvey a false and distorted portrayal of their past actions and detention by the Government'.

Besides referring to its classification guidelines to classify films, BFC also consults the Films Consultative Panel to ensure that our guidelines reflect community standards.

BFC provides explanations for its decisions on films. Film distributors and exhibitors can also approach BFC for more details. In addition, press statements are issued on films of wider interest to the public.

We welcome views and feedback and will continue to work with community advisory committees to ensure that our film guidelines reflect community standards.

Amy Chua (Ms)

Director of Media Content

Media Development Authority

==========================

April 20, 2007

Film bans: Detailed reasons, please

By Ken Kwek

The Straits Times

IF YOU'RE any kind of artist based in Singapore, you will find there is only one thing worse than having your work banned: not knowing why it was banned in the first place.

I have had some experience of this. From 2003 to 2005, when I was in Britain, I co-produced and shot a documentary called The Ballad Of Vicki And Jake.

The film chronicles the life of Vicki Harris, a heroine addict struggling to bring up her 11-year-old son, Jake, in a home racked by social dysfunction and abuse. Shot over 18months, it was a labour of love - and horror - for American director Ian Ash and me.

So far, the film has been screened in six countries and was recently picked up by a Canadian distributor. Last June, The Arts House agreed to show it here in what would have been the movie's Asian premiere. I gave a copy to event organisers, who duly submitted it to the Media Development Authority (MDA) for classification.

By August, programmes had been printed and screenings planned for late September. All that remained was for the MDA to give us the go-ahead. Which it didn't. This was three weeks before the planned screening.

The Arts House appealed on my behalf, but to no avail. In an e-mail, the MDA 'agree(d)...that the film portrays the negative repercussions of drugs', but nonetheless wanted a four-minute scene with 'instructive drug use' cut out.

This was not a feasible option, and the screening was cancelled. I was disappointed because no detailed explanation was given as to why the scene, in which a character smokes a crack-pipe, was deemed 'instructive' - any more instructive than, say, the portrayal of a woman injecting heroine intravenously in the movie, Protege, which hit cineplexes here soon after.

I've recounted this experience in some detail to give a sense of the time and effort that often go into artistic work, and the shorter and seemingly opaque process in which such work is assessed by the MDA.

In 2004, film-maker Martyn See's Singapore Rebel, about opposition leader Chee Soon Juan, was pulled from the Singapore International Film Festival (SIFF) after organisers were told it could be deemed a 'party political film'.

The Ministry of Information, Communications and the Arts (Mica) later said in a statement that under the Films Act, such films - defined as any film that contains 'matter which is intended or likely to affect voting in an election', or that contains 'partisan or biased references to or comments on any political matter' - could result in a fine or jail term for the film-maker.

A group of 11 film-makers led by Ms Tan Pin Pin subsequently sent a letter to The Straits Times Forum page asking the Government for greater clarity on offences under the Act. Beyond arguments of free expression and artistic interpretation, her appeal was pragmatic: 'It would be a waste to spend resources making a film, only to find out it is unlawful because it has inadvertently run afoul of the Films Act.'

Her query was prescient.

Last week, Mr See's work was again banned and withdrawn from the SIFF. Zahari's 17 Years - on former opposition politician Said Zahari, who was arrested and detained under the Internal Security Act in 1963 - was censured for being an attempt to 'exculpate' Zahari from his past transgressions.

'The Government will not allow people who had posed a security threat to the country in the past to exploit the use of films to purvey a false and distorted portrayal of their past actions and detention by the Government,' Mica added.

This happened after the documentary had already been rated PG (Parental Guidance) for the Asian Film Symposium last year.

The film had also been withdrawn from that festival, after MDA officials met The Substation's artistic co-director, Ms Audrey Wong, and other festival organisers, and told them the material 'may be defamatory'.

These and other episodes, such as the recent withdrawal of another local film, Solos, from the SIFF, have created some tension between the authorities and the film community here. Dismay has manifested itself on two levels.

First, while censorship as an issue remains contentious for some, it is generally accepted as necessary by most, though the degree to which it is applied remains hotly debated.

Secondly, what has generated greater frustration, as recent examples show, is a more practical consideration: that those who decide what can be screened publicly need to be more consistent and conclusive in their assessment of films, because it is an economical practice that saves resources for all involved parties.

While few will quibble with the notion that censorship exists in all societies, the withdrawal of films from various events in recent years suggests a need for more accountability on how films are appraised.

What has frustrated film-makers and organisers here is less the principle of censorship than the exercise of it. Beyond the actual banning of films, what riles film-makers here is the inefficiencies of official assessment and sanction: the U-turns in the issuing of licences and classifications; the lack of specific direction on what sort of content is objectionable, as opposed to what 'may be defamatory'.

The authorities might well have reason to prohibit certain films if they are libellous or if they undermine public confidence in the Government. But when a film has been banned, the censors need to be specific - state exactly which scenes, characters, dialogue and so on were out of line - so film-makers, and the public, are left in no doubt as to the reasons behind the decision.

kenkwek@sph.com.sg

Post a Comment