Saturday, April 28, 2007

Film ban "ineffective and counter-productive"

By Loh Chee Kong,

TODAY Posted: 27 April 2007

SINGAPORE: The decision by the Ministry of Information, Communications and the Arts — and its use, for the first time, of the Minister's discretionary powers — to ban a film based on the arrest and detention of a former journalist and politician throws up a number of questions.

Why ban the film, Zahari's 17 Years, when it was passed with a PG rating not once but twice last year, to be screened at the Singapore International Film Festival and the Substation's Asian Film Symposium?

Neither organiser screened the film and it was reported that the Media Development Authority had told the Substation that the film may include defamatory content.

Why ban the film when the memoirs of Mr Said Zahari, a former editor of the Malay language newspaper Utusan Melayu and president of Parti Rakyat Singapura, are available in bookshops here?

As the 77-year-old told AFP: "What I said in the movie I have already said in my book, and much, much more."

Why create unnecessary curiosity and drive people online to watch the film, which has already found its way on to the Internet?

In today's wired world, it is more likely than not, the ban will be ineffective and counter-productive. Minister Mentor Lee Kuan Yew said as much recently: Censorship in the Internet age "makes no sense".

Indeed, a movie has a wider and more evocative reach than a book, since voice, motion, drama and images do tend to have a bigger impact on shaping the minds of audiences — which is why different rules must apply to different media, especially on issues that could get the viewers worked up.

I saw the film before the ban. It gave an account of Mr Said's arrest and detention days — including his recollection of taking Chinese lessons from a fellow detainee. He said he was not a foreign agent, nor a communist sympathiser. He also spoke critically about Mr Lee, when asked for his take on why he was detained.

Mica said that the film gives a "distorted and misleading" portrayal of Mr Said's arrest and detention and "could undermine public confidence in the Government". The film, it added, was "an attempt (by Mr Said) to "exculpate himself from his past involvement in communist front activities against the interests of Singapore".

Most Singaporeans recognise a good government — and a flat lie for that matter — when they see one. If the authorities were worried about whether the audience would be discerning enough to separate the wheat from the chaff, they could have given the film a higher classification rating.

If the intention was to send an unequivocal message, there are better ways to do so, including a rebuttal of the false accusations.

The Government has every right to take a stand against what it feels is a distorted account. If it felt that an open rebuttal would raise the film's profile unnecessarily — which it has inadvertently already done with the ban — the authorities could impose, as a condition for screening, a "government advisory" at the start or end of the film, to refute any misleading statements.

Actually, this was a great opportunity for the Government to engage Singaporeans on an important part of the country's history.

The tumultuous period from the '50s right through the '70s, with its backdrop of riots and demonstrations, can arguably be described as the defining period of nationhood.

These events, which were openly documented by newspapers, shaped the Republic's relatively short but no less rich history.

Yet, our school children do not get a good grasp of these events from our history textbooks — the same sources that described the '50s Hock Lee bus riots as having been primarily fuelled by dissatisfaction with long work hours and low pay.

Some researchers and historians have offered other possible reasons for the riots, such as anti-colonial sentiments and instigation by pro-communist quarters.

It is not that these accounts are not available here. One can go to the Internet, visit libraries and bookshops, attend forums — like the one held last year by former political detainees Messrs Tan Jing Quee and Michael Fernandez — or even get second-hand accounts from their parents or grandparents, to piece together this important chapter of the Singapore story.

Censorship is a double-edged sword, especially in today's YouTube world, where privacy is constantly under threat.

Allow anything and everything and you are likely to have an uncontrollable situation on your hands. Cut and censor and you will have a population hungry for the forbidden fruit.

So, how do we move forward?

Engage Singaporeans, let contrarian views find their voice and challenge the views of those who have different accounts.

The Government took a rare and bold move to debate ministerial salaries openly in Parliament, although it was not duty-bound to do so. Singaporeans wrote in to newspapers to give their views, not all of them agreeing with the Government.

Censorship deserves a similar airing. I can't think of a better way forward. - TODAY

----------------------------------------------

Further readings

Digging into foundations is mischief

Defending the national scripture

Now S'pore copies M'sia: Bans another film

Tuesday, April 24, 2007

RSF urges Singapore to lift ban

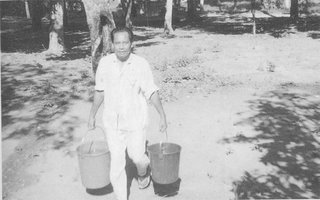

Said Zahari in forced exile on Pulau Ubin, 1979

Said Zahari in forced exile on Pulau Ubin, 1979SINGAPORE, April 24, 2007 (AFP) - A press freedom group called Tuesday for Singapore to reverse its ban on a film about a former political detainee.

Paris-based Reporters Without Borders (RSF) said the ban was "another authoritarian measure violating press freedom" in the city-state. Singapore banned the film on former detainee Said Zahari, calling it a"misleading and distorted portrayal" of his detention which could undermine confidence in the government.

The film "Zahari's 17 Years" was directed by Singaporean filmmaker Martyn See, who had earlier been investigated by police for making a film on opposition leader Chee Soon Juan.

"The ban on See's film must be lifted," RSF said in a statement.

"This act of censorship is all the more inappropriate and ridiculous as his films are available on websites," it said.

"We call for the liberalisation of the censorship and internal security laws that deprive Singaporeans of an environment favourable to free speech."

Singapore's ministry of information said See's film "gives a distorted and

misleading portrayal of Zahari's arrest and detention under the Internal Security Act in 1963."

It called the film "an attempt to exculpate himself from his past involvement in communist united front activities against the interest of Singapore."

In the film, the elderly self-exiled journalist, poet and author reflects on his 17 years in detention.

Singapore has often been criticised by human rights and media groups for maintaining strict political controls despite its rapid economic modernisation.

But the government says the strict laws are necessary to maintain law and order -- a pillar of the country's economic prosperity.

On Friday, producers of a Singapore film about a man and boy struggling with their mutual sexual desire said they had withdrawn it from public screening at the city-state's film festival.

The decision to withdraw "Solos" came after Singapore censors made three cuts to scenes depicting homosexual and group sex, the Singapore International Film Festival (SIFF) told AFP.

----------------------------------------

RSF's Press Release

AP report

Monday, April 23, 2007

All this censorship makes no sense : MM Lee

Minister says gay sex should be legal

Singapore must remain cosmopolitan to survive: MM Lee

A cold, hard reality check

Sunday, April 22, 2007

'Zahari's 17 Years' now online

The full 49 minutes of 'Zahari's 17 Years' is now available for viewing on Google Video. (Updated to youtube) I hereby declare that it wasn't uploaded by me as I've surrendered my remaining master copy to the censors on 11 April. Prime suspects should include festival organisers, film buffs, academics, historians, journalists, ex-detainees, all and sundry who may have seen the film or even possessed copies of it at one time or another.

Of course I can't direct you to the link as I will then be culpable of distributing a prohibited film which does carry a jail term. It first appeared in one of the 'Local Voices' blogs on the right column of this page.

Meanwhile you can watch this ITN news clip of the ban which features a rare appearance by former student leader Tan Wah Piow, a political exile residing in UK.

Saturday, April 21, 2007

Film ban strange, says Said Zahari

Malaysiakini

Apr 11, 07 3:31pm

Ex-political detainee Said Zahari is surprised by the Singapore government’s decision to ban a documentary film entitled Zahari’s 17 years directed by Martyn See.

Said, who is the former editor-in-chief of Utusan Melayu, said the main reason could be that Singapore does not want its younger generation to know the political history of the state during the 50s and 60s.

Said, who is the former editor-in-chief of Utusan Melayu, said the main reason could be that Singapore does not want its younger generation to know the political history of the state during the 50s and 60s.“The (Singapore) government is afraid that more and more people will know about the nation’s history,” he added when contacted today.

However, Said, who was detained for 17 years, also said the move to ban the film was surprising because it has been around for the past one year.

He said the film has been distributed in many countries and it is strange why the Singapore government decided to ban it now.

Among others, the film has been screened in Malaysia and Canada.

“I have not seen the (Singapore) government’s statement but I don’t understand why they want to ban it only now?” he asked.

According to Said, what he had revealed during the 50-minute film was just a minor portion of what he had written in his book Dark Clouds at Daw published in Malaysia in 2001.

Security threat

A Reuters report yesterday stated that Singapore’s Ministry of Information, Communications and Arts had banned the film because it went against public interest.

“The film gives a distorted and misleading portrayal of Said’s arrest and detention under the Internal Security Act (of Singapore),” said the ministry.

“The film gives a distorted and misleading portrayal of Said’s arrest and detention under the Internal Security Act (of Singapore),” said the ministry.It claimed that the film was an attempt by Said “to exculpate himself from his past involvement in communist united front activities against the interests of Singapore.”

The ministry said the film had to be banned because it posed a security threat as it sought to undermine public confidence in the government.

The film’s director has been asked to turn over all copies of the film by Singapore’s Media Development Authority.

Previously, See was investigated by the Singapore police after he produced a documentary about opposition leader Chee Soon Juan in 2005.

Government bans film on journalist detained without trial for 17 years

Country/Topic: Singapore

Date: 20 April 2007

Source: Southeast Asian Press Alliance (SEAPA)

Person(s): Martyn See, Said Zahari

Target(s): other

Type(s) of violation(s): banned

Urgency: Threat

(SEAPA/IFEX) - The Singapore government has banned an independent film about a former top journalist and political activist who was held without trial for 17 years in the island republic, deeming the documentary to be "against public interests".

"Zahari's 17 years" by local filmmaker Martyn See is a 49-minute interview with Said Zahari about his arrest and subsequent detention under the draconian Internal Security Act in 1963.

In a statement on 10 April 2007, the Ministry of Information, Communications and the Arts announced the ban under the Film Act, saying the documentary was an attempt by Said "to exculpate himself from his past involvement in communist united front activities against the interests of Singapore".

"The government will not allow people who had posed a security threat to the country in the past to exploit the use of films to purvey a false and distorted portrayal of their past actions and detention by the government," the ministry said, adding that this may "undermine public confidence in the government."

However, Said's political memoir, "Dark Clouds at Dawn", on which the film interview is based, is available in local stores. Said is most famed for staging a three-month strike against a political takeover of the then-leading nationalist newspaper, "Utusan Melayu", of which he was editor-in-chief in 1961. He failed to prevent the takeover, but earned a place in the history of Malaysia and Singapore for leading the first and, until today, only journalists' strike over the principle of press freedom.

"Zahari's 17 years" is not listed in the Media Development Authority's database of classified films, although reportedly given a PG (parental guidance required) rating twice in 2006, when it was submitted for screening at the Singapore International Film Festival in January and a film symposium in August. On both occasions, the film was never screened, with no reasons given. An application for an exhibition licence in January 2007 was abandoned midway, and the ban followed three months later.

As the ban covers exhibition, possession and distribution of the film, See surrendered his master copy to the censors on 11 April. However, the film can be viewed at: (Do a search on google video - Martyn)

This is the second documentary by See to be banned. In 2005, police investigated him for 15 months after he produced "Singapore Rebel", which documents the trials and tribulations of opposition leader Dr Chee Soon Juan, who has been imprisoned repeatedly for exercising his right to free speech and sued for defaming present and past prime ministers (see IFEX alerts of 26 September, 31 August, 11 May and 23 March 2005).

Bizzare ban on Pak Said film in Harry's S'pore

Taken off the blog of Malaysian journalist James Wong Wing-On

Those who have read Singapore's former PM and SM, MM Lee Kuan Yew's memoirs know for sure that the name of Said Zahari never appears as a historical record, let alone the reason or reasons for his 17-year detention without trial under Lee's premiership. Now, according to the Ministry of Information, Communication and Arts of Singapore which has recently banned a made-in-Singapore historical documentary about Said Zahari, the latter was allegedly involved in what is said to be "communist united front activities against the interests of Singapore". However, my friend Amir Muhammad's films Lelaki Komunist Terakhir and Apa Khabar Orang Kampung which documents the stories of self-identified hardcore and real communists like Chin Peng, Abdullah C.D, Suriani Abdullah, Abu Samah and other can still be screened and watched publicly in Singapore. Said Zahari, the trilingual former editor-in-chief of Utusan Melayu whose computer was stolen from his Subang house together with the manuscript of the last installment of his trilogical memoirs during last year's Christmas vacation, of course, now lives in Malaysia as my cherished neighbour, good friend and esteemed sifu .

Tuesday, April 10, 2007

Zahari's 17 Years - rated PG by censors, banned by Minister

The above documents were delivered to my home this afternoon. One is a public statement while the other is a letter specifically addressed to me.

Both documents basically dictated the same message - that as of April 12 2007, the film 'Zahari's 17 Years' will attain the same illicit status in Singapore as a copy of Playboy or FEER. Anyone caught in possession or distribution of the material will be liable on conviction to a fine or imprisonment. The public statement did not spell out the penalties but the letter to me most certainly hit home the point.

The public statement also made no mention of the fact that the Minister himself has banned the film under Section 35(1) of the Films Act, which basically accords absolute discretionary powers to one person to decide if a film is suitable for public viewing. This is unlike the case of 'Singapore Rebel', which was deemed to have violated Section 33 which bans political films with "biased references". I was told by a Straits Times reporter earlier that this marks the first time that Section 35 has been evoked to ban a film.

Further, in the public statement, it said that I had submitted the film for classification, as if it was the first submission. Indeed, I had gone to the Board of Film Censors on January 11 this year, but it wasn't for the purpose of classification. I was there to make an application to obtain an exhibition licence to screen the film. I was made to understand that a film passed by the censors does not entail a licence to screen it publicly. A separate permit is required.

Here it gets a little screwy.

'Zahari's 17 Years' was first submitted to the Board of Film Censors by the Singapore International Film Festival around March of 2006. Information obtained from MDA by journalists at Today and ZaoBao indicated that the film had been passed clean with a Parental Guidance (PG) rating. Yet, the SIFF did not screen it, and has refused to disclose any reason for the no-show.

Then the Asian Film Archive decided to make another application to screen the film as part of the Substation's 6th Asian Film Symposium in September. Again the film was passed clean with a PG rating (see document on the left). But again the festival organisers withdrew the film with no official explanation.

It was on the premise that the film had already been cleared twice by the censors that I decided to apply for an exhibition licence on January 11, only to be slapped, three months later, with yet another ban.

The Government has shown itself incapable of engaging in any kind of open dialogue on its dark history of detentions without trial. It has refused to acknowlege the fact that the ISA has been used in many instances to achieve its political ends. And interestingly, despite its regurgitation of Said Zahari as a former security threat, the international press continues to tag him a former "political detainee".

__________________________________________________________

Singapore bans documentary about former political prisoner

Tanalee Smith

Published: Tuesday, April 10, 2007

SINGAPORE (AP) - Singapore said Tuesday it would ban a documentary about the 17-year detention of a former leftist activist because its "distorted and misleading" portrayal of the events could undermine confidence in the government.

"Zahari's 17 Years" is a 49-minute interview with Said Zahari, who was arrested in 1963 on suspicion of plotting violent acts and detained without trial for 17 years. Said, 78, now lives in Malaysia.

The Ministry of Information, Communication and the Arts, which vets all films before release, said in a statement that the film was an attempt to clear Said of his involvement in activities against Singapore.

"The government will not allow people who had posed a security threat to the country in the past, to exploit the use of films to purvey a false and distorted portrayal of their past actions and detention by the government. This could undermine public confidence in the government."

Filmmaker Martyn See, who was under investigation last year for a documentary about an opposition leader, said he was surprised by the ban. He said the film, produced at the end of 2005, had been approved twice last year with a PG rating. When it was not shown at the 2006 Singapore International Film Festival, as he expected, See applied for an exhibition licence to screen it publicly.

"I don't know what changed. Maybe different people with different views watched it this time," See told The Associated Press. "I based my questions to Said on his first book, which is sold in Singapore. So what is in the film is not something the government didn't know."

He said he had been ordered by the censorship board to surrender all copies of the film by Wednesday afternoon.

Said, contacted by telephone at his home in Malaysia, was shocked to hear of the ban. He said he had already accepted an invitation to come to Singapore next month to give a speech at the film's screening by a university film institute.

"This is very funny. I don't understand why they would ban it at all. What I said in the movie I have already said in my book, and much, much more," he told AP. "That was 40 years ago. Is the government still afraid?"

"I feel sorry for Singaporeans who have not been given a chance to see the other side of Singapore history, particularly the 1960s and '70s. It's not fair," he said.

Said's detention came in the early years after British colonizers gave self-government to Singapore in 1959. In the early 1960s, authorities arrested left-wing politicians, trade unionists and Chinese students involved in strikes and rallies, accusing them of being violent subversives planning a communist state.

Said was detained on Feb. 2, 1963, hours after he was appointed president of a left-wing party.

Singapore, which was planning a merger with what later became Malaysia, said the swoop was aimed at individuals threatening to use violence to sabotage the proposed amalgamation. The detainees were jailed under the colonial-era Internal Security Act, which allows for arrest without charge and indefinite detention without trial.

Said, who denied the accusations, was held for years, sometimes in solitary confinement, after the merger failed in 1965 and Singapore became independent.

He was released in 1979, at age 51. A stroke in 1992 left him reliant on a walking stick and prompted his move to Malaysia, where his children had relocated.

The banning of "Zahari's 17 Years" under the Film Act prohibits exhibition, possession and distribution of the film.

The film's director, See, was investigated by police last year concerning a documentary he made about an opposition leader. He was given a "stern warning" but could have faced prison time or a fine if convicted of knowingly producing and distributing a "party political film."

That film, "Singapore Rebel," was screened at film festivals in New Zealand and the United States, but not in Singapore.

Amnesty International criticized Singapore for that case against See, saying the city-state was stifling artistic freedom and preventing citizens from expressing dissenting views.

Singapore authorities tightly restrict media and political speech, moves that regularly draw criticism from international human rights groups. Prime Minister Lee Hsien Loong has acknowledged tensions over the regulations but defended them as necessary to maintain order.

Singapore bans film about ex-political detainee

Reuters

Tuesday, April 10, 2007; 9:05 AM

SINGAPORE (Reuters) - Singapore is banning a film about a former political detainee who was held for 17 years without trial to protect public interests, the government said.

The film "Zahari's 17 Years" about former journalist Said Zahari -- arrested in 1963 for suspected subversive activities, including communist sympathies -- will be banned because it is "against public interests," the Ministry of Information, Communications and the Arts said on Tuesday.

"The film gives a distorted and misleading portrayal of Said Zahari's arrest and detention under the Internal Security Act," the Ministry said in a statement.

"Zahari's 17 Years" is directed by local film director Martyn See, who was investigated by the Singapore police for a year after he produced a documentary about opposition leader Chee Soon Juan in 2005.

Singapore, which is frequently criticized by human rights groups for its restrictions on the opposition and media, bans political films that contain "biased references to or comments on any political matter."

See said he has been asked to turn over all copies of the banned film on Tuesday by Singapore's Media Development Authority, which has also rejected his application to screen it in the city-state.

"Zahari's 17 Years" is a 50-minute long interview with Zahari about his 17-year detention -- one of the longest in Singapore -- and the fear among former political detainees to talk about their experience, See said.

"The government is clearly not allowing history to be heard. It does not want to acknowledge the history of detention because it is an acute embarrassment," See said.

The film has been screened in film festivals in Malaysia and Canada, he said.

The Ministry said "Zahari's 17 Years" was an attempt by Zahari "to exculpate himself from his past involvement in communist united front activities against the interests of Singapore."

"The government will not allow people who had posed a security threat to the country in the past to exploit the use of films to purvey a false and distorted portrayal of their past actions and detention by the government," the ministry said, adding that this may "undermine public confidence in the government."

Thursday, April 05, 2007

Lee-fearing Nation

"Ordinary people do not fear the Internal Security Act as much as they fear that if they voice criticisms against the government they will be punished in ways that can directly affect their livelihoods. Shopkeepers and taxi-drivers worry their licences will be revoked, and businessmen whether big or small, have the same apprehension. Civil servants fear their independent views on public matters will deprive them of promotions or get them transfers to insignificant ministries or the ultimate punishment - loss of employment. The press fears. The police fears. The ISD (Internal Security Department) fears. The army fears. The PAP MPs fear. And the ministers fear...Everyone fears Lee."

- T.S. Selvan, author and former ISD officer

"Between being loved and being feared, I have always believed Machiavelli was right. If nobody is afraid of me, I'm meaningless."

- Lee Kuan Yew, Oct 6, 1997

Lee's Legacy

Lee's Legacy

Opinions of Lee in the country are many. More often than not they are a curiously alternating vocabulary of praise and criticism. As his talents and gifts are many and unusual, so are some of his defects. They tell on the way people view him when in their different moods. When people are angry, they forget his merits, and when are happy, they ignore his faults. He then becomes the only barrier between man and chaos. He is glorified to a point where it is said that since God has forgotten to endow the country with any natural resources, he redresses the oversight by giving Lee to the country.

Some are genuinely caught in a moral dilemma because as they condemn of some of his shortcomings they cannot easily overlook his outstanding contributions to their material well-being. He has not been a mindless despot like some of the Third World politicians. Some, however thankful they are, still find it hard to morally excuse him for treating his political opponents with an almost neurotic disapproval and condemnation. He is accused of binding everyone to his system while he himself stays out of it. Even the Godless think he plays God. But they do not say whether God is a dictator.

But what is the long and short of it? Where does Lee stand? Curiously, what will Lee himself think of his role as he continues to lead his flock? Will he be chuffed by his admirers' adulations? Will he be stung like Prometheus by the diatribes of his critics? Or does he have his hopes pinned on history's final judgement?

To look back. When the British finally left the island, the migrants invested Lee with the power of sovereignty and they expected this sovereignty to be used in their rights and interests. The migrants did not wish the bossy and holier-than-thou colonial type authority. That phase was over. It was time, the migrants rightly thought, to belong and identify, to participate and be counted. It was in recognition of this right that the Sahib had also returned the island to the people.

Lee took over. Democratic politics immediately became an irredeemable sin; a political perversion. An Easterner by upbringing and a Westerner by education, a Machiavellian by instincts and a Zarathustran by genes, he at once concluded that a state could neither be run on Judeo-Christian virtues nor by any airy-fairy Western liberal exhalations. He sought authority in the way the East and governments of all larger states had been ruled before the British, American and French revolutions. Lee must have also picked up some handy habits from his early partnership with the communists. Communism, which believes that the state is a divine idea, subsumes the complexities of human experience under a rigid collectivist and monolithic order - one single will, one single state, one single party rule. More importantly, the communists' faith in the grave philosophy of the end justifying the means became a lethal weapon in Lee's hands. Not to forget, once in power, the communists do not capitulate; they want to rule forever.

As soon as he took over he made his people recognise and accept without question the absolute sovereignty of the state which became synonymous with his own sovereignty. The man and machine became one. He smashed all threats to his power. As ends and means became entangled in his politics so were the problems of the state and his own became enmeshed into one and the same. He fustigated the communists, set the dogs on a free trade union movement, and closed the doors on a free press. The communalists and racists had to be flattened because they subverted the nation. Many of his political opponents were kicked around like dogs. Some yielded entirely and became his willing poodles. To his credit, there has never been an instance of political killing in three decades. When this fact was pointed out to a Westerner, a frequent visitor to the country, he said, "When you have detention without trial, your problems disappear very fast. You don't have to worry about wanting to make people disappear."

To sustain and legitimise his moral authority he constantly emphasised the weaknesses of man. He could call up at will historical precedents, imperatives, and cruel memories of a dark age. Unquestionably, he created a permanent sense of crisis. Again and again he went back to the question of the country's security: He warned of the shortage of natural resources and the smallness of the country. He reminded people of the divisive racial and linguistic pulls, and fretted nighmarishly of Humpty Dumpty going to pieces. To a migrant society without permanent security and without much education, these fears, real as they were, became dangerously real. So fearing the decay, and fearing Lee's Leviathan, they fearfully accepted his authority. Here it must be said that although Lee is a propagandist, he actually believes, one thinks, in what he says about the past and the calamitous history of the country. But if the purpose of the propaganda is to teach, it is also intended to sustain his own power.

Lee is completely and consumately absorbed with power, but no leader can continue to hold on as long as he has and be counted credible if he does not deliver. People in the end get tired of fine talk. When the masses get tired, no fear, no tyranny, can hold back the bursts. And this is where Lee is unequalled by many other authoritarian rulers. It is from his ability to pay well that most of his arrogance and invincibility stems which in turn moves his politics. As he made people fear his political ruthlessness, he also shared his extraordinary gifts as a professional businessman; a first-rate achiever. As fast as possible, he gave as much as possible. It was a bang-up job. A materialist, he believed that facts and figures shout louder than slogans.

As he continued to deliver, he also continued to erect comprehensive social policies, his Facts of Life, to consolidate society. He never tolerated state welfarism, never allowed self-indulgence, insisted on hard work, tabooed pornography, told parents to discipline their children, drilled the youths in the army, admonished the people to uphold the family system, kissed the jury system goodbye, ordered the police to administer proper justice to the criminals, hang the heavy peddlars of dope, campaigned for the people to bow their heads in courtesy, urged his people to take better aim in public toilets, and guide their saliva into a spittoon.

"I am often accused of interfering in the private lives of citizens. Yes, if I did not, had I not done that, we wouldn't be here today. And I say without the slightest remorse, that we wouldn't be here, we would not have made economic progress, if we had not intervened on very personal matters - who your neighbour is, how you live, the noise you make, how you spit, or what language you use. We decide what is right. Never mind what the people think."

- Prime Minister Lee Kuan Yew, Straits Times, 20 April 1987

Lee-fearing society

Lee-fearing society

In short, Lee has so far created from irrelevance a successful society where economic security and social order flourish. This in itself is an extraordinary tour de force but the setback to the system is the lack of political liberty. This appears to be Lee's biggest failure. Foreign critics are not quite out of touch with Singapore when they describe it as a "city of fear". The fear is real, and it is not just at the top-layer of people's feelings. It is deep. Worse, people are sometimes terrified out of their wits. Worse still, there is a lot of fear but no courage.

Ordinary people do not fear the Internal Security Act as much as they fear that if they voice criticisms against the government they will be punished in ways that can directly affect their livelihoods. Shopkeepers and taxi-drivers worry their licences will be revoked, and businessmen whether big or small, have the same apprehension. Civil servants fear their independent views on public matters will deprive them of promotions or get them transfers to insignificant ministries or the ultimate punishment - loss of employment. The press fears. The police fears. The ISD (Internal Security Department) fears. The army fears. The PAP MPs fear. And the ministers fear. No joke. Once in the mid 1980s, a senior civil servant went to discuss certain aspects of a policy decision with a minister. The minister said, more or less, that he was willing to say what he really thought about the decision but was reluctant to do so because it could be carried to the Old Man's ears. ...Everyone fears Lee.

The perception of fear is something that refuses to go away. More often than not some of these fearful people exaggerate (before they do this they look to the right, left, and over their shoulders) their self-importance and value by attributing their personal failures to having the guts (imagined, of course) to go against some of the government policies. As much as fear is real in the country, this group of self-important people is also real. Most of these people can be found predominantly among top civil servants, university lecturers and business elites.

Young yuppies who may have the inclination to go into opposition politics are hesitant because they, among other things, think that the government with its powerful machinery will rake up past indiscretions, however silly they are, and distort them into acute public embarrassment. We are here talking about PAP gutter politics. There is also the fear that the government will continue to hound them in the future through other means. The concern is valid because the record of the government is unhelpful to its image. On the other hand, some use this fear as a convenient excuse for not entering politics. Life, you must remember, is bountiful under Lee.

As fear threatens the people, something else is beginning to scare Lee and his government. The society is slightly more complex now than it had been a decade or two ago. Wide diffusion of English education, economic opportunities, the power of machine, social mobility, and exposure to other political viewpoints, are all conspiring to shape the political attitudes of the citizens. In other words, Lee's very success is working against him.

The young are particularly resentful of the way they are being governed : control, yet more control. Look, it is happening again, they sneer. They feel that the over-administration of the classroom suffocates creativity and individuality. They are gradually beginning to reject Lee and his moral prophecies because they suspect the perpetual hand of a controller yet again trying to manoeuvre his way through to increasing his own glory and power. Although they were born and bred under the PAP regime, they are beginning to break free like rebellious adolescents often do. Lee is not their king. Youth, with its idealism and energy, is Lee's greatest threat.

Nurturing indifference

How long can a government continue to suppress real discussion and be intolerant of mediocrity? How long could it avoid compassion and caring for the really under-privileged? How can a society hope to mature and progress if there is little political intelligence and awareness? Can political loyalty to the system be taken for granted when the people are suspicious that Lee and his party control all the rules of the game? Perhaps there is a question to ask: could Lee himself, presuming that he is an ordinary man (i.e. not a politician), live in such a society without being too constrained and unhappy? Could he bear to see his prime minister enjoying all the freedom while he is denied it?

The kind of political system that is found in the country is bound to nurture indifference. When the citizens, if the government so decides, can be arrested without the due process of law, it strikes fear. It erodes loyalty. The government urges the different races to be tolerant and to harmonise their relationships to build a nation together but its own intolerance of critics and differing viewpoints is seen as Double talk. The government is happy when the press, whether local or foreign, pleases it but comes down vindictively when it ceases to praise. When a foreign press criticises the government it is accused of involving itself in the political process but when its own citizens, those who think differently, question and challenge some of its policies, they are being put down for the very act of participation. For example, immediately after the 1984 general elections, the government seemingly opened up the system and invited discussion and feedback. When the Law Society of Singapore attempted to do just that (the Law Society sought to persuade the government to change its mind about the Amendment Acts to the Press, and it did not encourage the citizens to disobey or break the law - there is a big difference here) it was disgraced out of court. One of its members was kicked around like a ball. Can a system be thought of a great success when it brings unnecessary pain to others?

Lee's Singapore or the Singaporean's Singapore?

Why is Lee, given the intensity of his Superman vision, so obstinate in his heroism in not wanting to allow for real democratic changes? Power is just part of the explanation, though a good part of it. But more importantly, is Lee certain of his vision of the future? Will he be proven right and others wrong in the end?

Lee has no God but he cannot give up playing God. He will always think he is right. That is his destiny; his own star to follow. "If there are gods," exclaimed Zarathustra, "how could I bear to be not a god?"

His adversaries who do not like Lee and his politics and would like to see him go, will have a mountain of a task to crush him. Their Macbeth is not ripe for shaking, yet. And one thing appears certain. Whether you like him or not, Lee is a legend. If Raffles was the taker of Singapore, Lee certainly is the creator, and a better story to tell. For the moment one hesitates to place him alongside the other Asian greats - Gandhi, Nehru, Mao - although intellectually he could claim equal, if not better depth. Using a different scale, if one gives Pol Pot 1, Marcos 3, the late Sukarno 5, Tengku Abdul Rahman 7, Lee gets a 9. If either of the scales does not fit that must be because Lee is quite clearly in his own league.

Before Singaporeans reach their own decision on their most famous legend and his creation, are they themselves clear in what they want of society, of life? Do they think someone else could do a better job? With the same per capita income, jobs, houses, schools, hospitals, roads, snazzy cars, snappy clothes, but more democratic politics. What is their dream of an ultimate island? If people are inclined to accuse Lee of becoming an island unto himself, are they becoming an island unto themselves? Are they themselves naively prone to over-emphasise their own importance and wisdom (and I don't write this with any kind of sneer or cynicism) as Gibbon, the great historian, thought the Greeks did? Commenting on the Byzantium, Gibbon said: "Among the Greeks, all authority and wisdom were overbonne by the impetuous multitude, who mistook their rage for valour, their numbers for strength, and their fanaticism for the support and inspiration of Heaven."

Human societies appear hopelessly destined to a cyclic process of growth, decay and disintegration. But a good vision is said to change or delay this process to some extent. Without this vision a society perishes quickly and when that happens all the King's men could not put back Humpty Dumpty. The poetry will made short. It is a dance of death on a narrow wall.

On the first day that he took over the leadership of the island from the white man, on 3 June 1959, Lee told his semi-colonised people: "Once in a long while, in the history of a people there comes a moment of great change..." The change has come, but is not great. The quintessential Lee Kuan Yew's Singapore (it should not happen, but it does) must be turned into Singaporean's Singapore. We must hope for the real Lee Kuan Yew to emerge over a period of time.

- T.S. Selvan, 1990